“We all have stories, we all have voices, and they all deserve to be heard”

– Robert X Fogerty, Founder Dear World

As our current series explores the Narrative Universe, we wanted to look at the work of Dear World, a unique organization dedicated to the power of personal storytelling. Below is an interview with Executive Producer, Jonah Evans in which he describes their distinctive approach of enlisting the human body and portraiture in the storytelling process.

MD: At Dear World, you say, “We aren’t changing the world, but we take pictures of people who are.” For people unfamiliar with the Dear World project, can you tell us what it is all about?

JE: Dear World is a portrait project that unites people through pictures and stories. It began in New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina. At the time we thought maybe the last chapter in our city’s history had just been written. In those early years of recovery, we asked people to share love notes to the city of New Orleans. However, we asked them to share those notes by writing the message on their skin—and then we took their portrait. The urgency of those years translated into incredibly intimate, honest, powerful, vulnerable stories of love, loss, hope, and fear. We realized these were not just New Orleans stories, but human stories. So Dear World evolved into an international portrait project. It is part journalism, part art project, part facilitation—all focused on the process of having these images be a way to connect to one another through the stories of what matters most to us.

MD: You ask people to write the core message of their personal story on their body, on their skin. Why the body?

JE: The first step in the process is that we ask you to share a message to someone or about something that you care about and, yes, to have that message written on your skin. We found that asking something of people that is both open-ended and constrained—it must be contained on your body, you must be willing to commit the message to your body—creates a really powerful moment of reflection for people. MD: After the message is written on your skin, then there is the expanded storytelling followed by the portraiture?

MD: After the message is written on your skin, then there is the expanded storytelling followed by the portraiture?

JE: Our work is done in a group setting and the first part of sharing the story comes from the fact that you do not write the message on your own body. It is written on you by someone else – in a public setting. This could be a stranger, or a fellow-student, or a colleague. This process creates a surprisingly intimate moment, one that starts slowly peeling away the layers of the onion. The story surrounding your message is supposed to come out organically. We don’t rush it. The portrait is the byproduct of the process, not the focus.

MD: It strikes me that portraits always imply a story, but by adding text you provide a different way in for people.

JE: I have noticed that oftentimes photographers feel in control of creating a subject’s story, but in our process we cede control to the subject. Our job is to be a mirror, to reflect back what is most essential. The fact that the subject literally chooses the message you see is a key component of that. And, as you say, it allows the viewer to start to access the subject’s personal story. MD: How do individuals experience your process? As cathartic? Meaning making? You’ve worked with people ranging from celebrity athletes and Noble Prize winners to local residents, students, and company employees. Are there commonalities to the experience?

MD: How do individuals experience your process? As cathartic? Meaning making? You’ve worked with people ranging from celebrity athletes and Noble Prize winners to local residents, students, and company employees. Are there commonalities to the experience?

JE: Certain reactions play out again and again. There is the reflective moment: what are the stories that propelled my life to this moment? There is the moment of doubt: do I feel comfortable sharing my story? And once the story is shared, there is a feeling of truly being heard, of connecting. We are struck by how deep people go and how quickly they do so. Everyone has a story to tell and everyone has a desire to be heard. A new intimacy occurs even in settings such as college campuses or corporations where you might think you already know someone.

MD: Can you give an example of this?

JE: We once worked with a finance organization, with a group of hard charging, high-performing alpha males. There was a man named Paul who appeared not to be participating. But when we approached him, he took off his shirt to reveal his bare chest with a defibrillator and a message that said “I survived a heart attack and now I save lives.” In a silence in which you could hear a pin drop, Paul told his story. Everyone knew he left work early on Wednesdays, but he was pretty standoffish and no one asked him about it. A few years ago he had a heart attack while in traffic and an EMT was in the car behind him and saved his life. After coming to, he found that EMT, got trained as one himself, and now Wednesday nights he goes out and saves live. This was a revealing story about Paul and what makes him tick and it was amazing how his colleagues responded and how relationships he had had for years changed and deepened with its telling.

MD: Paul’s story is a powerful example of the ways that storytelling can change perceptions of colleagues and create more meaningful connections. But this all hinges on people’s willingness to be vulnerable enough to tell their tale, which can be particularly hard in a work setting.

JE: There is something magnetic about storytelling. So we just try to model good storytelling for an organization, and pretty soon everyone wants to give it a go. In corporate settings this often means asking leaders to tell their stories first. On college campuses, we start with a small group of students first, and as soon as they put their stuff up on social media, other students flock to the shoot.

MD: Again, it’s clear from the example of Paul that connections are created through your storytelling process. How do you maximize these connections in large group settings?

JE: After doing a shoot, we often reconvene as a large group and highlight particular stories that reflect something of the participant body. At a biomedical company, for example, the stories that come out are often about the personal reasons that led individuals to work in the industry: “I work here because my father died of cancer.” In the wrap-up we’ll give people a chance to reflect on the commonalities of their individual stories. This creates powerful interconnections—not only between people, but also between the personal and work aspects of each individual storyteller.

MD: I would imagine that this process would lead people to view their colleagues, their organization, and the work they do together in a much more thoroughly human ways.

JE: Good stories always reveal our common humanity. And it’s easy to lose sight of that in a work context. Again, if you work in biomedicine, much of your daily work is technical, so you can forget the heart-driven aspects of your work. Stories ask you to remember to see, hear, and feel the human impact. MD: Dear World’s work conveys a strong sense of hope and resilience. You’ve highlighted stories of survivors of the Boston Marathon bombing, the tornado in Joplin Missouri, Hurricane Sandy, and Syrian refugees. Was there a conscious decision to underscore certain themes?

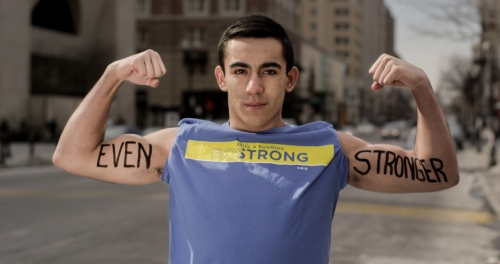

MD: Dear World’s work conveys a strong sense of hope and resilience. You’ve highlighted stories of survivors of the Boston Marathon bombing, the tornado in Joplin Missouri, Hurricane Sandy, and Syrian refugees. Was there a conscious decision to underscore certain themes?

JE: I think stories of hope and resilience are built into the DNA of Dear World because we began in the wake of Katrina.

MD: One powerful example of resilience is captured in the field study you did with survivors of the Boston Marathon bombing.

JE: At one of our Boston photo shoots we met Dave Fortier. In his first portrait he wrote the word “Healing” over his left ear. It emerged that Boston had been Dave’s first marathon and he was 100 feet from the finish line when the bombs went off. Since then a ringing sensation has persisted in his ear. When asked him about how one comes back from an experience like that, he invited us into a community of survivors. A large group of survivors agreed to come back to the site of the bombings, the site of the finish line, to share their messages, tell their stories, and take their portraits. The power of a community coming together around shared stories of pain and resilience was staggering.

MD: There is a humility written into your claim: “We aren’t changing the world, but we take pictures of people who are.”

MD: There is a humility written into your claim: “We aren’t changing the world, but we take pictures of people who are.”

JE: Well, it’s very humbling to work with people telling such stories of hope and resilience. It’s humbling to see the way that these stories know no barriers of race, age, geography. We are coming up on our fifty thousandth portrait and we are still learning. We can’t wait to see where Dear World will take us next.

Back